|

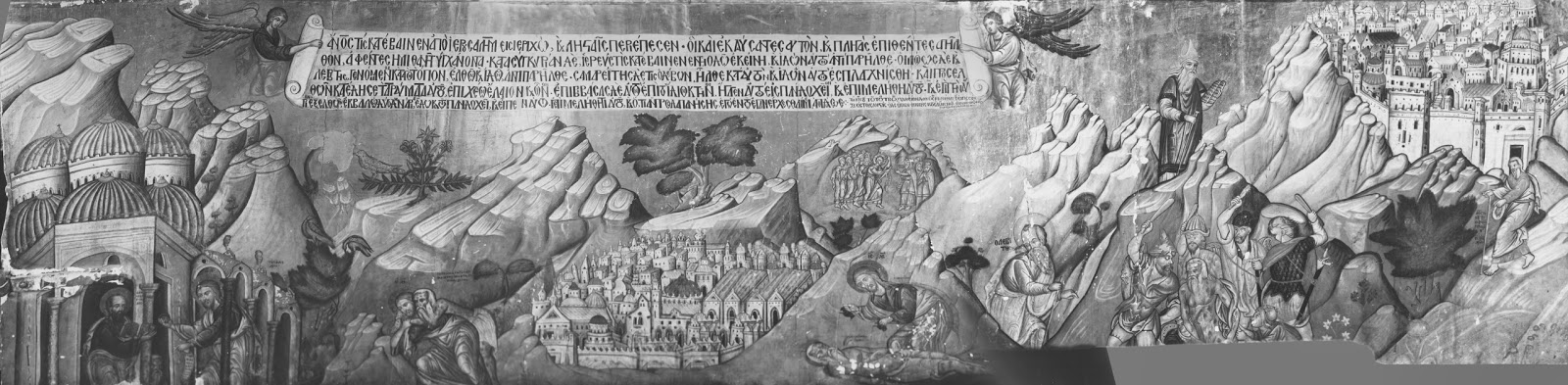

| Good Samaritan mural, St. Catherine's Monastery (14th century) |

Can you find the Good Samaritan's "animal" (Luke 10:34) in the above mural? The answer is below.

I guess I'll finish with a discussion of the one parable interpretation of Augustine that virtually everyone knows: the parable of the Good Samaritan. Before I get to his famous allegorical interpretation, however, I'll briefly talk about some of his other readings of the parable. I will also discuss the above 14th century mural of the Good Samaritan at the end of this post, because it shares Augustine's allegorical understanding of the parable.

Augustine’s most famous parable interpretation is his allegorical

reading of the parable of the Good Samaritan, one which follows those by

Irenaeus, Origen, and Ambrose, who see the Samaritan as symbolizing Christ healing

the wounds caused by sin and who detect numerous other allegorical details in

the parable. Less well known, however, are Augustine’s non-allegorical citations

of the parable. Sometimes, for example, Augustine interprets the parable as a

moral example of the universal nature of Christian love: “Every human being is

a neighbor to every other human being” (Sermon

8.2; cited by Teske 2001: 348). Likewise, Augustine’s Sermon 299 interprets the

parable as a moral example to teach

that every human being should be a neighbor to every other human being and to

act as the Samaritan acted. In addition, Augustine discusses the moral

application of the parable to admonish his readers that Christians must speak

the truth, even to non-Christians, because we are “neighbors” of every human being,

Christian or non-Christian (cf. Against

Lying, Section 15, discussing Eph. 4:25).

Augustine also notes that this love for our neighbors

extends to our enemies and even speculates whether that love extends to angels

as well—the answer is yes (On Christian

Doctrine 1.30.31). Then, however, Augustine moves to the “deeper” meaning

of the parable: “For our Lord Jesus Christ points to himself under the figure

of the man who brought aid to him who was lying half dead on the road, wounded

and abandoned by the robbers” (1.30.33). Augustine elaborates this symbolic

aspect of Jesus as the Good Samaritan in several other texts, because he

believes that the attacked man’s descent from Jerusalem to Jericho necessitates

a spiritual interpretation in addition to the moral one. We should desire to

“ascend” in contrast to the man who “descended” and then fell among thieves

(Luke 10:30), but Jesus, as the Good Samaritan, “slighted us not: He healed us,

he raised us upon his beast, upon his flesh; he led us to the inn, that is, the

church; He entrusted us to the host, that is, to the apostle [Paul]; he gave

two pence, whereby we might be healed, the love of God, and the love of our

neighbor” (Exposition on the Psalms 126.11).

An extensive example of Augustine’s spiritual interpretation

of the Good Samaritan parable is found in his Questions on the Gospels (2.19). He begins by arguing that

A certain man went down from

Jerusalem to Jericho; Adam himself is meant; Jerusalem is the

heavenly city of peace, from whose blessedness Adam fell; Jericho means

the moon, and signifies our mortality, because it is born, waxes, wanes, an

dies. Thieves are the devil and his angels. Who stripped him,

namely; of his immortality; and beat him, by persuading him to sin; and

left him half-dead, because in so far as man can understand and know God,

he lives, but in so far as he is wasted and oppressed by sin, he is dead; he is

therefore called half-dead. The priest and the Levite

who saw him and passed by, signify the priesthood and ministry of the Old

Testament which could profit nothing for salvation. Samaritan means

Guardian, and therefore the Lord Himself is signified by this name. The binding

of the wounds is the restraint of sin. Oil is the comfort of good

hope; wine the exhortation to work with fervent spirit. The beast

is the flesh in which He deigned to come to us. The being set upon the beast

is belief in the incarnation of Christ. The inn is the Church, where

travelers returning to their heavenly country are refreshed after pilgrimage.

The morrow is after the resurrection of the Lord. The two pence

are either the two precepts of love, or the promise of this life and of that

which is to come. The innkeeper is the Apostle. The supererogatory

payment is either his counsel of celibacy, or the fact that he worked with his

own hands lest he should be a burden to any of the weaker brethren when the

Gospel was new, though it was lawful for him “to live by the gospel” (Dodd

1961: 13-14; slightly abridged).

In Augustine’s interpretation, almost everything has a

symbolic meaning. Jerusalem, for

example, designates the physical city of Jerusalem and the spiritual “heavenly city of peace.” Like Origen, Augustine

also appeals to the etymology of Samaritan,

notes its connection to “guardian,” and specifically connects it to Jesus as

“guardian” in this parable (cf. Ps. 120:4), a claim, he argues, made by Jesus

himself. Thus this parable, for Augustine, becomes symbolic of Jesus’

incarnation and the process of redemption of human beings, which explains the

identifications Augustine makes in the rest of the parable’s details (Teske

2001: 350). Augustine even postulates additional symbolism in other

interpretations, such as the “Apostle/innkeeper,” being “perhaps” Paul (Tractate on John 41.13; for other

examples of his allegorical readings, see also: Sermon 69.7; Sermon 81.6;

Tractate on John 43.8.2).

Many visual representations of the parable of the Good Samaritan reinforce the allegorical interpretations of Irenaeus, Origen, Augustine, and others that the parable symbolizes fallen humanity, Satan’s attacks, the Law’s inadequacy, and Jesus’ mercy. See, for example, my earlier discussions of the 12th century stained-glass windows in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Chartres. Similar allegorical interpretations in stained-glass windows can be found in the Cathedral of St. Etienne in Bourges, the Cathédrale Saint-Étienne in Sens, and the Canterbury Cathedral (see also my earlier posts about the Rossano Gospels).

Likewise, a 14th century mural in St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai (the image at the top of this post) labels the Samaritan as “Jesus Christ” (IC XC). Just as in Augustine's allegorical interpretation, Jesus (as the true Good Samaritan) attends to the wounded man (i.e., Jesus restores fallen humanity to a right relationship with God, which the old dispensation--symbolized by the priest and Levite--cannot provide) and brings him to the "inn" of the church.

The above mural takes the allegory even further, because, as you can see above, Jesus himself (as the Samaritan) carries the wounded man (fallen humanity) to the inn (the church), instead of placing the man on an animal. This action emphasizes the sacrifice of Jesus; he is the “beast of burden” who bears upon himself the salvation of humankind.

The mural also includes other interesting elements, such as Moses on a mountaintop holding the Ten Commandments. Perhaps I should devote an entire blog entry on this mural sometime soon.

For those of you who read German, an excellent book on this subject is: Ayado Hosoda, Darstellungen der Parabel vom barmherzigen Samariter (Petersberg 2002).

Many visual representations of the parable of the Good Samaritan reinforce the allegorical interpretations of Irenaeus, Origen, Augustine, and others that the parable symbolizes fallen humanity, Satan’s attacks, the Law’s inadequacy, and Jesus’ mercy. See, for example, my earlier discussions of the 12th century stained-glass windows in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Chartres. Similar allegorical interpretations in stained-glass windows can be found in the Cathedral of St. Etienne in Bourges, the Cathédrale Saint-Étienne in Sens, and the Canterbury Cathedral (see also my earlier posts about the Rossano Gospels).

Likewise, a 14th century mural in St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai (the image at the top of this post) labels the Samaritan as “Jesus Christ” (IC XC). Just as in Augustine's allegorical interpretation, Jesus (as the true Good Samaritan) attends to the wounded man (i.e., Jesus restores fallen humanity to a right relationship with God, which the old dispensation--symbolized by the priest and Levite--cannot provide) and brings him to the "inn" of the church.

The above mural takes the allegory even further, because, as you can see above, Jesus himself (as the Samaritan) carries the wounded man (fallen humanity) to the inn (the church), instead of placing the man on an animal. This action emphasizes the sacrifice of Jesus; he is the “beast of burden” who bears upon himself the salvation of humankind.

The mural also includes other interesting elements, such as Moses on a mountaintop holding the Ten Commandments. Perhaps I should devote an entire blog entry on this mural sometime soon.

For those of you who read German, an excellent book on this subject is: Ayado Hosoda, Darstellungen der Parabel vom barmherzigen Samariter (Petersberg 2002).

Grandma has a family/group lesson based on the story of the good Samaritan. You’ll find it here:

ReplyDeletehttp://mygrandmatime.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/3-who-and-how-we-serve-can-surprise-us.pdf

My parish in the name of st augustine, i never thought that this much god's grace he have.thank you Jesus for this wonderful gift.

ReplyDelete